Title: Doctor Who and the Green Death

Televised as: The Green Death

Written by: Malcolm Hulke

Teleplay by: Robert Sloman and Barry Letts

Screen Credit to: Robert Sloman

Televised in: May/June 1973

Published in: August 1975

Chapters: Ten and Eleven

“This machine kills fascists” – Woody Guthrie’s guitar

“A maggot is a perfectly ordinary creature, even if these are two feet long. They revolt you because they make you think of things that are rotten and decaying.”

Only one Welsh character appears in the back third of the novelization of The Green Death. She’s largely apolitical – she’s a cleaning lady – but her name is Blodwen, and her husband is Rhys, in case you missed the Welsh thing. But, after most of the overt politics and the Welshmen have been dispensed with, Malcolm Hulke gets down to the business of giving you, the likely eight- to twelve-year-old reader, sitting there in 1975, exactly what you want to read. Less Clifford Odets, and more carnivorous maggots.

Like any egg-born creature, the maggot inside has started as an embryonic speck floating in the fluid that was to be its pre-birth food. In a matter of days the embryo had absorbed the fluid, growing in the process.

Now all the fluid was gone, and if the maggot was not to die it had to escape. Instinctively it arched its back, heaving against the walls of the egg. And then, suddenly, the egg cracked open. The maggot lay exhausted from its efforts. Then it sniffed sharply. It was experiencing a new source of energy – oxygen in the air around it. It wriggled its little body, and realized it was quite strong. It also realized it was very hungry, and that it now had to find its own food.

Hulke gets into that maggot’s head eerily well, right? Later Target books would stretch the narrative format in all sorts of interesting ways, with Eric Saward in the novelization of The Visitation telling a scene from the viewpoint of a badger, and Ben Aaronovitch in the novelization of Remembrance of the Daleks telling scenes from the POV of Davros, a Dalek, a shuttlecraft, and a planet. Well, they can all thank Hulke for pioneering that approach. And, in his next book after this one, Hulke is going to write scenes from inside the pea-sized brains of dinosaurs (who, as it turns out, say things like KKLAK! But that’s a story for another day).

Hulke then pivots to the POV of a mouse, which ends about as well as you’d expect.

It was, the mouse thought, something that could be eaten, for it too was hungry. The mouse went up to the face of the maggot, and then the maggot struck. Its jaws opened and the mouse was killed instantly.

The maggot wriggled about the floor in happiness. During all its existence inside the egg, it had lived on liquid. Now, inside it, was flesh, and the sensation was wonderful.

*****

Professor Clifford Jones comes to life, too. He’s the man who will serve as Jo Grant’s deliverance from Doctor Who, and he’s consciously set up as a younger version of the Doctor. Jo falls in love with him merely from his newspaper clippings:

“There’s a man called Professor Clifford Jones who’s fighting against Panorama Chemicals. He needs all the support he can get. So I’m going to help him.”

“I’ve heard of that man,” said the Brigadier. “He’s an impractical dreamer.”

Jo tucked the newspaper neatly under her arm, ready to go. “So, sir, were Jesus of Nazareth, Christopher Columbus, and Marconi”.

Cliff is a bit of a Doctor surrogate, an off-putting know-it-all with a big heart. He tells the Brigadier in the book that there’s no proof that cigarette smoking causes lung cancer, as there’s nothing you can prove in a laboratory”. The Llanfairfach locals view him as a limousine liberal, speaking textbook Welsh out of Cardiff when all of them have forgotten how to speak it. But the miners’ subplot to the story ends, in the book, with Dave Williams “speaking in Welsh to show that he now accepted Professor Jones as one of the villagers”, so hard has Cliff worked to protect and defend them against the horrors of Panorama Chemicals and the Green Death.

It takes the Doctor time to realize that he’s losing Jo to Cliff. Pertwee delivered a lovely line in Episode One on TV, about the fledgling flying the coop, bit that was evidently added late in production to give Pertwee one of his patented moments of charm. In the book, the Doctor doesn’t figure it out until late in the Episode Four material, and Hulke handles the heartbreak so well that it’s a a shame he didn’t live long enough to write teen-angst dialogue for all those prime-time soaps on the CW Network thirty years later.

He drew from his pocket the beautiful blue sapphire. “I got this from there. Like to see it?”

She glanced at the precious stone. “Great,” she said, and turned back to the book. “Well, goodnight, Doctor.”

The Doctor had never known Jo to be like this before. In their many travels together they had always been very close. No one had come between them.

Later in the same scene, he intentionally blocks Cliff from meeting up with Jo, and feels “an almost childish satisfaction at spoiling her date. When Professor Jones came back the Doctor put his arm round the younger man’s shoulder and led him away.”

But this segues into Jo getting a ferocious voice of her own, in a way that Terrance Dicks usually didn’t allow her to have:

“He knows I’ve fallen in love,” she thought to herself. She felt rather sorry for the Doctor, and wondered why he had never married. Were there, she wondered, lady Time Lords? Did Time Lords get married and have babies? How old was the Doctor? She realized there were many things she didn’t know about him.

Jo gets to use the word “topless” in the book, too, which you have to assume is some sort of in-joke as to what sort of things Katy Manning got up to shortly after she left the program. More relevant to the story, Jo and Cliff get their first kiss earlier in the book than on TV:

“There,” he said. “I’ve been trying to get the courage to do that. Are you terribly angry?”

She swallowed hard “No, not at all”. She was rocking on her heels with happiness.

“Good,” he said. “I’m glad you didn’t mind.”

Another great book-only Jo moment sees the Doctor utterly failing to mansplain science to Jo:

“We think of the earth beneath our feet as being packed tight, but it isn’t, really. Apart from mines there are caves, even rivers running underground. I don’t think this was man-made.”

“Human-made, if you don’t mind,” corrected Jo.

“What?” The Doctor had gone on ahead and now turned back.

“People say “man-made” as though men are the only people who ever make anything. There are also women, and I’m one of them.”

But Hulke gives the Doctor triumphant bits, too (in addition to the usual capacious pockets):

“Do you normally break into private property, especially when you’d be more than welcome arriving at the front door?

“I do very little normally,” said the Doctor, “unless that is the quickest way to go about things. In this instance, an abnormal approach seemed more fitting”.

Hulke also carries off the rare feat of having the Doctor come up short in an argument with Dr. Stevens; the Doctor “realized he had lost on that score and quickly moved to another approach”. But he mostly speaks in effective poetry; when Captain Yates ask why BOSS’ planned “ordered world society with everyone happy and well-fed” is a bad idea (a precursor to what Yates will do in his next TV story), the Doctor points out that “Their price of plenty is eternal slavery”. When using the blue Metebelis crystal to un-brainwash Yates, the book’s Doctor gets to rattle off an almost Sylvester McCoy-esque speech of intricately linked non-sequiturs:

“It is necessary for you to see something, Captain Yates.”

“Necessary?” repeated Yates.

“For increased efficiency,” said the Doctor. “For improved-balance-of-payments, let-my-people-go, strength-through-joy, peace-in-our-time,” he went on, reeling off nonsense to confuse Yates, “you must see what I have in my pocket.”

On TV, it takes the Doctor a while to use Professor Jones’ feverish utterance of the word “serendipity” to unravel the plot, but in the book the Doctor gives us the whole etymology of the word, “coined by a chap called Horace Walpole, after the fairy-tale called The Three Princes of Serendip”.

When the Doctor kills the first (and last) of the venomous green-death flies at the end of Episode Six, in the book he gets to expound more on the tragedy of what he’s done:

“It was trying to kill you,” said the Brigadier.

The Doctor, rather sadly, got back into Bessie. “And we were trying to kill it, Brigadier.” He looked up the slope at the mass of dead maggots. “Whatever they were, they thought they had a right to live”. He started Bessie’s engine, and slowly drove away from the scene of the carnage.

“You know,” said Sergeant Benton, “I’ll never understand the Doctor. He’s always so sorry in the end for the horrible creatures we come across. It isn’t human.”

“You’re forgetting,” said the Brigadier, “he isn’t”.

*****

This fascist machine kills.

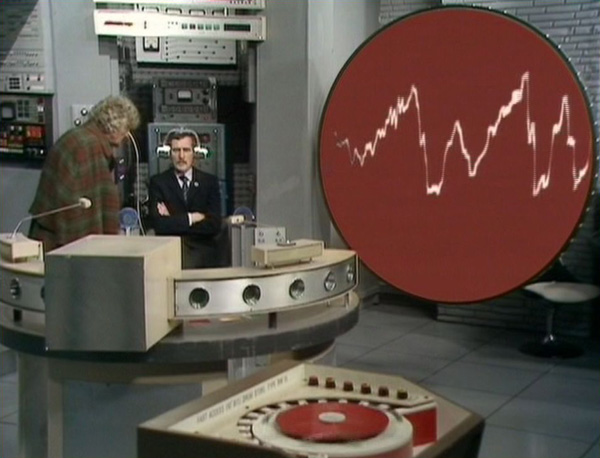

When BOSS arrives on the scene, we see Hulke do something we’re not used to him doing – being funny. BOSS’ entry into the story is a bit tonally jarring, as we suddenly go from hard left-wing politics and environmental crusading, to a comedic computer that’s been programmed to think illogically, which is just minutes away from creating a world-wide web (sorry) of mind-control, only a few years after WOTAN tried to do the same thing in The War Machines. On TV, the Doctor calls BOSS a megalomaniac, but, in the book, BOSS proudly describes himself that way, and also demonstrates “an excellent Welsh pronunciation” of Llanfairfach.

Hulke gives Boss more overt Nazi parallels; on TV, BOSS made several unsubtle allusions to Wagner and Nietschze, but in the book he actually quotes Adolf Hitler, which triggers in Stevens memories of being terrified by Hitler’s voice on the radio as a child. However, BOSS does less singing in the book, which is one loss.

And what does BOSS want? As Captain Yates is being led off to total processing by BOSS in the Episode Six material, before he escapes, Dr. Stevens in the book has extra dialogue, telling Yates exactly what’s going to happen:

“You will become a slave,” said Dr. Stevens. “you will have no mind or will of your own. But, like any well-cared-for animal, you will be very happy. For a number of hours each day you will work, and for the rest of the day you will eat, or sleep, or sing merry songs. And you will have no worries about anything.”

“God gave Man the right of free will,” said Yates.

“True,” agreed the Director, “but it causes so much trouble. Wars, people going on strike for higher wages, all sorts of social problems. We shall create a new order in which everyone will be content.”

Hulke also uses the Wholewheal community (the Nut Hatch, in the book, or Nut Hutch, on TV, as you prefer) to have a few laughs, perhaps, at Professor Jones’ collection of environmentalists. Hulke writes these characters in a similar way to his community of celebrities “escaping” Earth in Invasion of the Dinosaurs, although this crew is decidedly less homicidal:

The long haired ex-colonel in the kaftan and beads looked out from the living room. […] “And do you mind making less noise? I’m composing a poem for peace.”z

“Sorry, sir,” Benton leaped to attention.

“Just call me Jeremy,” said the ex-colonel, and went back into the living room.

*****

Of course, it’s not a Hulke book with a lot of condensing, especially in the wafer-thin Episodes Five and Six material, with whole scenes of TV action condensed into a paragraph of recollections. However, the fate of Hinks – the Panorama Chemicals thug attacked by a maggot in Jo’s place in the resolution to the Episode Three cliffhanger – is explicitly revealed in the book (he died), where it’s left more open-ended on TV.

At the conclusion, Hulke adds more explicit pathos to Dr. Stevens death; in the book, Stevens narrates his choice to sacrifice himself by blowing up BOSS, to whom he’s still connected. This gives the Doctor the questionable moral choice which is glossed over on TV:

The Doctor looked on, wondering if he should lift Stevens bodily and carry him to safety. But he thought better of it. Perhaps it was kinder to leave Dr. Stevens to die with the computer, the only “friend” he had ever trusted.

The answer to that is, of course, “No, it isn’t”.

But you’re not getting out of the book without a moment of final heartbreak, as Jo leaves the Doctor (and the series) to marry Cliff. The final scene in the book is staged slightly differently on TV; we’re missing the Doctor giving Jo the Metebelis crystal as a wedding present (even though it’s needed to bridge the gap with the next novelization, of Planet of the Spiders, which opens with Jo returning the crystal), and we’re missing Jo getting her influential uncle to fund Cliff’s community with UN money. Without those distractions, all we get are the tears.

The Doctor looked at Jo’s fair hair and pretty face. They had traveled a great deal together, through Time and Space, and he had learned to love her very dearly. He found it difficult to accept in his heart that he might never see her again. There was a sudden stuffiness in his nose and he knew that his eyes were glistening.

As yours will be, too. Thanks, Mac Hulke. He’d write three more novelizations after this one, all for his own stories, but this one, even though it’s not his, is probably his masterpiece.

Next time: Tears? You mustn’t cry. Remember, while there’s life, there’s.

I like The Green Death. It’s well-written and well-acted, and it’s also one of the few Pertwee six-parters that doesn’t feel excessively padded out to death.

Nice in-depth look at the novelization. For years I actually thought Malcolm Hulke wrote the original serial, until I re-watched it when it came out on DVD. I agree, it seems so akin to his other serials that it was very appropriate that he was the one to novelize it.

In regards to Engin suddenly vanishing from the TV version and the previously-unseen James dying in his place, years later this was lampshaded by Mark Gatiss in his tongue-in-cheek mockumentary “Global Conspiracy” that was included on the DVD. Tony Adams reprised the role of Englin, and he reveals that he is a bit in the dark about what actually happened at Global Chemicals right before it was destroyed, because he fell ill and had to be rushed to the hospital just before it happened.

I am of two minds about BOSS. It is a great, dramatic, humorous “character” for Pertwee’s Doctor to spar with. At the same time, if BOSS is the one who is actually running Global / Panorama Chemicals, and all of the human employees are brainwashed pawns of it, then that pretty much absolves Stevens and the rest of any responsibility for the deaths and the horrible pollution they’ve caused. The story could have used some additional info. Who created BOSS? How long has he been in charge? Perhaps it should have been clarified that Stevens and his associates started the illegal dumping in the mines, and were influencing the government to turn a blind eye to their crimes, but their concerns were purely profit-minded, and that they created BOSS to increase efficiency & profits, only for the computer to seize control and decide to actually take over the world.

Yeah, the BOSS thing always struck me as an odd plot twist, a way of deflecting from the story’s politics. And, if I remember that documentary correctly, I think it suggests that Stevens actually survived the explosion at the end?

Pingback: Planet of the Buddhists | Doctor Who Novels