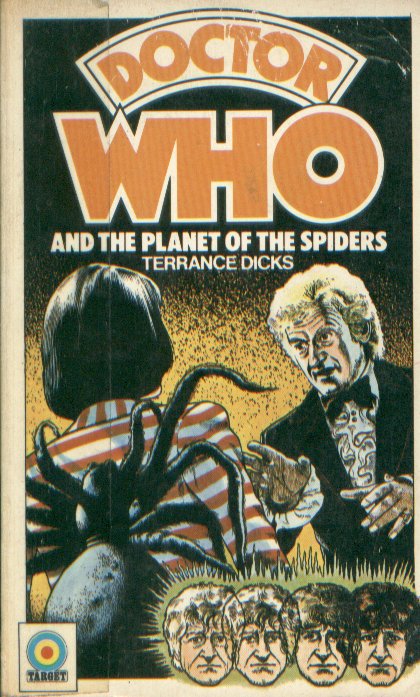

Doctor Who and the Planet of the Spiders. Original Target cover.

Title: Doctor Who and the Planet of the Spiders

Televised as: Planet of the Spiders

Written by: Terrance Dicks

Teleplay by: Robert Sloman and Barry Letts

Screen Credit to: Robert Sloman

Televised in: May/June 1974

Published in: October 1975

Chapters: One through Five

Part One of Planet of the Spiders is one of those deceptively leisurely episodes, in which seemingly nothing happens. The Doctor and Brigadier go to a dance hall to visit a series of cut-rate comedy, dance, and magic performances. Sarah Jane chases down a story from the disgraced Captain Yates, whom she barely knows, at a Buddhist monastery/retreat about a hundred miles outside of London. The story’s human villain, a tweed-clad unemployed salesman named Lupton, is seen dabbling in the darker Buddhist arts, but he’s a very low-key villain – much more low-key than the evil BOSS, whom Lupton actor John Dearth had voiced in the previous year’s season finale. You wouldn’t expect this story to unfold in the dramatic way that it later does.

Terrance Dicks tells us more than once that Lupton has “haggard, bitter features”, which hardly puts him on par with Daleks, Sontarans or Cybermen. But, to my mind, Lupton comes from a much more interesting place than those otherworldly monsters, and he proves a very interesting villain for the first half of the serial. For example, Lupton flashes Sarah Jane “a look of supercilious enquiry that verged on a sneer”. After taking a nap, Lupton “surfaced angrily from a deeply refreshing sleep, filled with dreams of vast, undefined power”. I’m not sure how those dreams work; I’ve certainly never had one. But few Doctor Who bad guys come from this white-collar background, and very few of them ever get to dream.

Lupton (John Dearth). Never given a first name, but the tweed blazer and Jack Nicholson hair is about all the characterization he needs.

*****

This is a book with no illustrations – after the pictures went away for the novelization of Robot, and then briefly came back, Alan Willow is gone from the line again, and no more Target books from here on out will ever bear internal pictures. But, of course, with Dicks’ sometimes lyrical writing, you don’t always need drawings. Dicks opens the book with a prologue featuring a mystery couple on an expedition deep within the Amazon, and we quickly learn that this couple is none other than Professor Clifford Jones, and his new bride, the former Josephine Grant.

(Actually, no, the book opens with a truly dreadful gag on the back cover blurb, with the Brigadier looking at the regenerating Doctor and saying “Well, bless my soul, WHO will be next?” But I digress …)

In fact, you could look at the novelization of Planet of the Spiders as the final installment in what you could call Target’s Jo Grant trilogy. While the books were published in basically random story order, here you have three releases in a row that, more by accident than design, tell Jo’s entire life-story – first, her TV debut, then her TV exit, and then, this bookend story to The Green Death, featuring a return to Metebelis 3, the return of the powerful blue crystal which the Doctor had taken in that earlier story, and, in the novelization only, one last time out for Jo Grant.

Terrance opens with one of his characteristically lush opening-pan paragraphs, even more cinematic than many of his other best efforts:

Night falls suddenly in the rain forests of the upper Amazon. One moment, the little clearing was bathed in greenish gloom by the light filtering through the dense carpet of the tree-tops overhead; the next it was plunged into darkness.

Speaking of “darkness”, Terrance gets to play around with the narrative a bit – this chapter is made of whole cloth, not appearing at all on TV – and flex his literary muscles. As we’ll see from the next two Terrance novels published immediately after this one, he’s not going to have a chance to do much more muscle-flexing after this. But, here, he has Cliff consider shooting his mutinous South American Indian porters (“His business was saving lives, not destroying them”). Plus, he gets one last dig in at the Welsh, after Malcolm Hulke got to spend the whole of the last book in Wales.

Languages came easily to [Cliff], and he was fluent in all the Indian dialects. Perhaps it was something to do with being Welsh, she thought. After that, all other languages must seem simple.

Unfortunately, the native tribesmen don’t come across too well – it’s still 1975 and Terrance really hasn’t embraced identity politics yet; the head porter here grunts rather than speaks, and the South American Indian tribe was noted to be head hunters “not too long ago”.

The reveal that this prologue is from Jo’s POV is kept as a surprise spoiler:

Josephine Jones, formerly Jo Grant, one-time member of UNIT, one-time assistant to that mysterious individual known only as the Doctor, propped the case on her knee, and began to write …

Jo doesn’t appear after the prologue, but when the Doctor receives her letter later in the Part One material, he reflects that “neither Jo’s grammar nor her handwriting had improved since she left UNIT”. There’s also a discontinuity here with the Green Death novelization, because here Jo is returning the Metebelis crystal, which Hulke never had the Doctor give her in that book. But, alas, that’s Jo’s final chronological appearance in Doctor Who until The Sarah Jane Adventures some 35 years later…

After the story proper begins, Dicks match-cuts (or, perhaps even better, slow-dissolves) Jo’s outro into Mike Yates’ intro:

Outside, in the gardens of the big old country house, Mike Yates, formerly Captain Yates, one-time member of UNIT, one-time assistant to Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart, ran through the darkness towards his car. He was more frightened than he had ever been in his life.

*****

The rest of the Part One material is Terrance firing off barbs of observational humor. Of a bad comedian at the dance hall, the Brigadier notes that was “talking very fast, as if afraid that the audience would make off before he could deliver his jokes. No one could blame them if they did, thought the Brigadier bitterly.” Of an exotic dancing girl, the Brig watches as “Fatima and her remaining veils undulated from the stage”. The Doctor builds “one of his own inimitable lash-ups of improved scientific equipment”, something you could imagine Dicks saying during a Pertwee-era DVD commentary 30 years later. Sarah wants to “crown [the Doctor] with one of his own Bunsen burners” when he ignores her, and also makes a comment about researching a story on “grass-roots resisasnce to property speculators”, which, as someone living in an area of Brooklyn with skyrocketing rents, hello, Sarah Jane, please come over here and tell our story.

Of course, there’s still time to be portentous: “Even the Doctor didn’t realize that his interest in Professor Clegg was to be the prelude to the most dangerous adventure of his life”. Often, that sort of line is false advertising used to make a run-of-the-mill story sound more breathless than it is… but this is the first of only five of the 160-odd Target novelizations in which the Doctor dies on the last page, so, in this case, Terrance is quite right to say so.

Clegg is written exactly as you’d expect for a character portrayed by the hapless Cyril Shaps, who played a string of similar characters throughout the Troughton, Pertwee, and Tom Baker eras. Dicks described his clothing as “shabby, and rather insignificant”, but tells us that the Professor (who’s not really a professor at all) “did his best to put a good face on things”. After the Doctor reveals that he knows about both of Clegg’s secrets (forged academic credentials, and secret ESP powers), Clegg “seemed to deflate, like a punctured balloon”. The book adds in an explanation for Clegg’s death – fright-induced heart failure – which was never provided on TV, presumably dropped for timing reasons.

Shaps, old chap.

*****

The book is also a bit radically restructured from the TV serial, as well, with several sequences invented or rearranged. As I’ve talked about in many of the previous novelizations from this era, the mid-1970s, books were often written from pre-rehearsal scripts, rather than from the final televised product or even shooting scripts. There are many books that contain more scenes, and more and better dialogue, than their TV counterparts. This is one of them, although not quite as radical a departure as Doctor Who and The Green Death has been. One loss is that Harry Sullivan is not mentioned – the book uses the name “Sweetman” as UNIT’s off-screen medic, a name which Nicholas Courtney changed during record in recognition of Harry having joined the regular cast in the concurrently-filmed Robot. As Robot had already been novelized, it seems that Dicks just plain forgot to change this line when transcribing out the rehearsal scripts.

One of the big changes here is that Cho-Je gets an additional scene in Part Two which was removed before filming, warning Captain Yates not to get involved with investigating Lupton’s evildoing. On the surface, Cho-Je is the TV story’s weak link – as in The Abominable Snowmen six years earlier, he’s an Asian character played by a Western actor in stilted makeup, and speaking entirely in fortune cookie slogans. When reading the print version of all those endless Buddhist riddles and Zen koans, one senses Terrance Dicks rolling a practical, world-weary eye at all of the philosophies that Barry Letts, the Buddist, brought to the production offices. Cho-Je is described with an “ivory-colored face” which “broke into a thousand tiny, smiling wrinkles”, and who speaks in a “clipped yet sing-song voice”. Later on, he “giggled disconcertingly”. Dicks also seems to get in some barbs at Letts leanings, observing in added dialogue, when Cho-Je talks about “the fullness of the void” or “The emptiness of the ten thousand things”, that “Sarah ahdn’t understood a word of it” (to which Cho-Je gigglingly replies, “Quite right! The Dharma that can be spoken is no true Dharma!”).

But, of course, at the end of the story, you learn that Cho-Je is not a Buddhist or Asian or even a human at all, so he comes across much better in print than all those one-dimensional monks that Terrance had written for a few months earlier.

The Doctor, of course, senses that something is lurking beneath Cho-Je’s placid surface, as the two men debate during the Part Three material:

Each of the two men was calm, polite and utterly determined. Under the unassuming exterior of the little monk, the Doctor could feel an intelligence and will that was a match for his own.

Tommy, the mentally challenged young man who serves as building porter at the monastery, is also described in terms that veer between sentimental and patronizing:

Tommy was a hulking, slow-witted youth, usually described as simple by his fellow villagers. He had worked at the monastery ever since it opened. Tommy was fiercely devoted to Cho-Je and his fellow monks – perhaps because they treated him with exactly the same quiet courtesy that they extended to everyone else.

Sarah also notes: “For all his size and obvious strength, his round blue eyes held the simple curiosity of a child”. All this material about Tommy will pay off much later in the book…

*****

In the Part Two material, the Spiders appear, and use Lupton as a vehicle for retrieving the Doctor’s stolen Metebelis crystal; they promise Lupton Earthly riches, of course never intending to deliver on that promise. Dicks cleverly describes the voices: “Then the spider spoke to him. Not out loud, of course, but inside his head. Her voice – somehow Lupton knew that the creature was female – was clear, sweet, and icily evil”.

The book uses a 12-chapter structure, which doesn’t quite adhere rigidly to the story’s six-part format – most of the cliffhangers come at the end of even-numbered chapters, with one exception. But you can sense Dicks stretching to force the material into this format; Chapter 3, for example, ends on a false moment of peril, with Lupton’s Spider warning him that he might have to kill the Doctor – a moment that isn’t included in the TV broadcast at all.

The much-derided chase scene, which takes up the back half of Part Two, is reproduced pretty faithfully in the book, with the Brigadier getting internal thoughts to help narrate for us exactly why the Doctor changes vehicles every few minutes. This is also the only Target book to feature Jon Pertwee’s flying car, the Whomobile, as Malcolm Hulke gleefully excised that vehicle’s only other appearance, when he novelized Invasion of the Dinosaurs a few books later. Dicks enjoys writing the chase, though; he slips into the head of a police officer, who gets to describe Sarah Jane as “a trendy-looking bird”, has the Doctor borrow some flying tactics from the Red Baron, and, of course, says:

The Brigadier had placated angry Prime Ministers in his time, but an English policeman in hot pursuit of a motoring offense was beyond his powers.

I’m going to assume that line was based on some real-life experience that Terrance had trying to talk his way out of a speeding ticket…

Next Time: Dicks transports us away from Earth at the end of Chapter 5, and most of the last four parts of the story will occur away from Earth, away from this planet of the Buddhists. The Spiders are coming, and so are some of the worst-acted and directed humans in the history of Doctor Who. Fortunately, Dicks proves superior to the material he was given to adapt, so the final seven chapters of the novelization are going to be far less painful that what we got on television…

…whence cometh “Next Time”? 😦