Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons. Original Target edition.

Title: Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons

Televised as: Terror of the Autons

Written by: Terrance Dicks

Teleplay by: Robert Holmes

Televised in: January 1971

Published in: May 1975

Chapters: One through Three

Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons is almost a perfect synthesis of the Target book line to date; it’s the 14th novelization overall, and the 11th one by Target, but it combines the best of all that’s gone before. This one is by Dicks, novelizing a Robert Holmes story, but is written very close to the style of Malcolm Hulke, the other mainstay of the early Target going.

Dicks does two things in this book that are positively Hulke-ian. First, there’s a chapter titled The Deadly Daffodils. This sounds almost exactly like the kind of Hulke and/or Dicks script that you’d have expected to see broadcast on The Avengers a decade previously, doesn’t it?

More importantly, you have the characterization. Terror of the Autons is the novelization of the debut story of Jo Grant and the Master. We’ve been both those characters in Target books before; both were introduced in Hulke’s Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon. But Dicks now gets to reintroduce them; the Master first, and then Jo.

Except that when we meet the Master here, it’s first through the eyes of a small-time thug who happens to run a circus; Lew Ross, who goes by the professional name Luigi Rossini. Dicks writes up Ross’ cynical biography, and this reads quite a lot like the exposition that Hulke writes for his secondary villains.

Rossini had his own way of making money. He hired only the deadbeats, the down-and-outs of the circus profession; those who for one reason or another could never get a job with the big, posh outfits. Some were too old, or too incompetent. Some, like Tony the strong man, were on the run from the police. Rossini hired them all, and paid them starvation wages, knowing they wouldn’t dare ask for more. All the profits went into his own pockets, paying for the flashy suits, the diamond rings and the big cigars that fitted Rossini’s picture of himself as international showman. Anyone who objected was soon beaten into submission by Rossini’s big fists. He had a right to his perks. He was the boss, wasn’t he?

But Rossini’s world is soon upended when the Master lands his TARDIS on the circus pitch, disguised as a horsebox (which Dicks of course describes as “gleaming”, in contrast to the shabby derelict vehicles that populate the Circus Rossini). And Rossini is both frightened of and in contempt of the Master, all at once.

Rossini saw a man of medium height, dressed in neat dark clothing. He had a rather sallow face with a small pointed beard, heavy eyebrows and dark burning eyes.

With a sudden flash of superstitious fear, Rossini thought the stranger looked like the Devil.

Rossini took a grip of himself. No funny-looking foreigner was going to frighten him.

The Master speaks in a “deep” voice, “full of authority”, and we feel Rossini go under the Master’s formidable hypnosis, from Rossini’s POV. That’s the end of Rossini’s POV for the rest of the book, though; once he’s put under the influence, we only ever see him again through Dicks’ omniscient observer …

*****

And soon we get a more formal introduction to the Roger Delgado Master. The Doctor is warned of the Master’s arrival by a Time Lord dressed like Patrick MacNee in The Avengers, and floating in mid-air. The Doctor here identifies him as a member of the High Council of the Time Lords. We also learn that the Master’s name is “a string of mellifluous syllables – one of the strange Time Lord names that are never disclosed to outsiders”. Or TV viewers.

Dicks also takes the time to fill us in on who the Master is meant to be, presumably drawn from his own papers as one of the Master’s unofficial co-creators. First, the Master’s genesis, envisioned as a Moriarty figure to the Doctor’s Sherlock Holmes, is openly quoted here, as the Brigadier refers to the Master as a “sort of criminal master-mind”. But we also get the following mission statement, incorporated into the text:

The Master was a rogue Time Lord. So too was the Doctor, in a way. But all his interventions in the course of history were on the side of good. The Master intervened only to cause death and suffering, usually in the pursuit of some scheme to seize power for himself. More than that, he seemed to delight in chaos and destruction for its own sake, and liked nothing more than to make a bad situation worse. Already he had been behind several Interplanetary Wars, always disappearing from the scene before he could be brought to justice. If ever he were caught, this fate would be far worse than the Doctor’s exile. Once captured by the Time Lords, the Master’s life-stream would be thrown into reverse. Not only would he no longer exist, he would never have existed. It was the severest punishment in the Time Lords’ power.

This latter bit was informed by The War Games, which was written before this book but novelized afterwards. Alas, we’ve never seen the Time Lords do this again, and the Master is still out there somewhere.

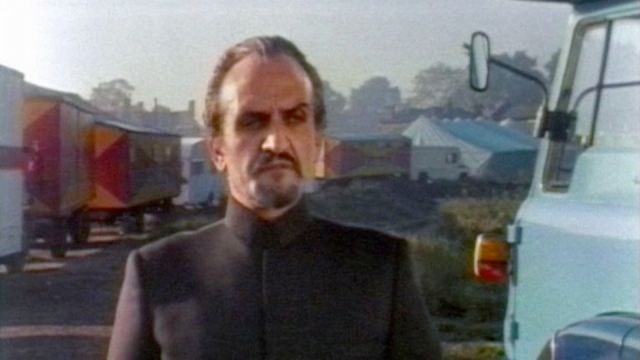

Roger Delgado as The Master. The original, you might say.

*****

We’d already seen Jo Grant before in the novelizations, and, in fact, the novelization of her fourth televised adventure doubled back in time and served as her formal introduction. But this is the adaptation of her real first time out, and so, we get, for the second time in a Target book, Jo meeting the Doctor. Terrance is not quite as sympathetic to the character as Mac Hulke had been, so he describes her faintly tongue-in-cheek:

As Jo Grant walked along the corridors of UNIT H.Q. she was bubbling over with an uneasy mixture of excitement and apprehension. At last she had achieved her ambition.

She was a fully fledged member of UNIT, the United Nations Intelligence Taskforce. The fact that she was the newest and most junior member of that top-secret organization did nothing to spoil her pleasure. But on the other hand she was about to meet the Doctor, and the thought of the coming encounter was enough to give her a mild attack of the shakes.

In Doomsday Weapon, Jo was patronized by her influential uncle when she asked for espionage training, but, nevertheless, she persisted. Here, however, she’s not quite in on the joke when the Brigadier foists her off on the Doctor, noting only that there “had been something almost amused in his manner …”. When Jo finally meets the Doctor, as on TV, he’s shockingly rude to her – and at his most stereotypical; it’s interesting to note that Dicks has Pertwee rubbing his chin not one, not two, not three, but five times in this novelization – far and away Dicks’ chin-rubbing record to date. Anyway, the Doctor’s not ready for a new assistant:

The Doctor looked down at her in speechless astonishment. He saw a very small, very pretty girl with fair hair and blue eyes, who looked as if she should still be at school. She seemed almost on the point of tears. “I’m sorry, my dear,” he said gently. “I really don’t think you’d be suitable.”

Later on, the Doctor likens Jo to a “puppy desperately hoping someone will throw another stick”. This is a line that hasn’t aged very well, although I think this is actually how Mitch McConnell described Elizabeth Warren in a tweet last night. Dicks also observes that Jo believes “modern intelligence methods failed to make proper allowance for women’s intuition”, which I’m not quite convinced is a compliment.

Dicks also gives us special insight into the warmly antagonistic relationship between the Doctor and the Brigadier. After Dicks as story editor and Barry Letts as producer began to remake the exiled-to-Earth format of Doctor Who in Season Eight, their first full season together, the Brigadier’s characterization on TV became slightly less rigidly military, and increasingly more buffoonish. Here, though, we find the Doctor and Brigadier in equilibrium, and, of course, it’s hilarious:

The Doctor and the Brigadier were engaged in one of their not infrequent arguments. Good friends though they were, their temperaments were so utterly different that the occasional clash was inevitable. This time the subject of dispute was the missing Nestene energy unit. The Brigadier, aware that he should never have allowed it to go to the museum, knew that he was really in the wrong. As result he was naturally insisting that he was completely in the right.

Dicks often gets a lot of flack from long-time Doctor Who readers for writing novelizations that were too short and too rushed, but it’s hard to question the talents of a guy who’s able to compress years and years worth of Pertwee’s and Nicholas Courtney’s TV chemistry into a paragraph this short and yet this note-perfect.

Also, because the dialogue in the book is so much more extensive than what we got on TV (presumably all scripted by Robert Holmes’ but trimmed for timing reasons), we also get this exchange, after the Doctor rapidly figures out what the Master’s up to at the space-telescope station:

The Director broke off, looking at the Doctor resentfully. “There really seems to be very little I can tell you.”

“There never is,” muttered the Brigadier.

*****

The plot begins in earnest when the Master, using Rossini as a strong-armed thug, steals a Nestene sphere left over from The Auton Invasion. In the book, dialogue is retained showing that the Doctor tested that sphere, from time to time, as a barometer to gauge if the Nestenes had returned to Earth. This is Terrance getting in his victory lap, triumphantly describing Pertwee’s first story and his own first novelization.

But in the hands of Robert Holmes, the Auton’s second invasion of Earth is no mere photocopy of Spearhead From Space. There are different plot beats here, and a much more jovial turn. The comedic poacher Sam Seeley took up quite a bit of time in the origin story, but here, instead, we get a comedy scientist who becomes a victim of the Master’s killing joke very quickly. Terrance digs into the mind of this character in a passage worthy of Malcolm Hulke himself:

Albert Goodge, a melancholy, balding, bespectacled scientist, drove slowly and cautiously as always along the narrow country lane, plunged in his usual gloom and lost to the beauty of the scene around him. It was a fine day in early summer. Fields and hedges lay bathed in sunshine, birds sangs, lambs gamboled; and Albert Goodge worried about the quality of his packed lunch.

As Goodge natters on for the third time about his hard-boiled eggs, his colleague, the equally doomed Professor Phillips:

hadn’t heard a word of all this. Goodge was always grumbling about something, and most of his colleagues had stopped listening long ago. […] Here in this tiny cabin they were listening to the voices of the stars. And old Goodge was grumbling about boiled eggs!

Goodge on TV was played by the lugubrious Andrew Staines (who’d return again for a less comic bit part in Pertwee’s final TV story), although Alan Willow’s internal illustration looks nothing at all like Staines. But Dicks goes from comedy to tragedy in narrating Goodge’s death from his own POV – one of the few times in the books that we’d feel what death by the Master’s Tissue Compression Eliminator feels like:

He caught a quick glimpse of a bearded man in the doorway, covering him with a squat, oddly shaped gun. There was a crackle of power and Goodge felt as if his whole body was being clamped in a giant fist and squeezed, squeezed. He seemed to be shrinking, rushing down the wrong end of a telescope into blackness.

*****

The Master has plenty of henchmen to keep him busy in this story, even after Rossini’s usefulness ends. The main dupe utilized by the master is Rex Farrel (a very young, pre-Davros, Michael Wisher), weak son of a domineering father, and inept head of a failing plastics’ factory. Dicks, as Hulke often does, constantly sounds the theme of just how inadequate Rex feels:

Rex settled himself in the big chair. Somehow, he always felt lost in it, swallowed up by its sheer size. As a child, visiting his father in this same office, he had been allowed for a treat to sit in the big chair and swivel it to and fro. He braced himself, sitting up straighter. Things were different now. At last his father had retired, and he was the boss.

But not for very long. The cunningly disguised “Colonel Masters” arrives, having selected Farrel’s factory as a spearhead for the Auton invasion because Farrel, “weak and indecisive… would make an excellent pawn in the Master’s game”. Dicks reminds us: “Dominated by his father all his life, conditioned to obedience from early childhood, Farrel was an easy victim”.

But the Master, of course, henchmen or no henchmen, won’t find such an easy time of it once he meets up with the Doctor …

Next Time: The second Auton invasion brings two things. Daffodils, and terror. And I’m fresh out of daffodils.

Pingback: The Deadly Daffodils | Doctor Who Novels

“a string of mellifluous syllables – one of the strange Time Lord names that are never disclosed to outsiders”

I really want the Doctor to describe his name like this in an episode at some point.

Maybe after Moffat leaves. The guy who titled an episode “The Name of the Doctor” and didn’t reveal anything (well, except for John Hurt).

Pingback: The Episode Four Syndrome | Doctor Who Novels

Pingback: Planet of the Buddhists | Doctor Who Novels